Italian Period

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Guido Bentivoglio, Seated (?), 1623

Brush and brown ink over black chalk (and graphite?)

15 5/8 × 10 3/8 in. (39.6 × 26.3 cm)

Musée des Beaux-Arts de la ville de Paris, Petit Palais, Paris

The most impressive of the few extant drawings for portraits from Van Dyck’s Italian period, this has traditionally been considered a study for the portrait of Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio, also in this exhibition. Despite differences in the pose, the thin face with mustache, goatee, and deep-set eyes and the spiky hem of the lace rocchetto help support this identification. The drawing’s size and use of black chalk underdrawing with bold brushwork set it apart from nearly every other portrait drawing by Van Dyck.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio, 1623

Oil on canvas

76 3/4 × 57 7/8 in. (195 × 147 cm)

Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence

One of the masterpieces of seventeenth-century portraiture, Van Dyck’s painting of Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio is renowned for the sensitivity of the sitter’s likeness, the elegance of the pose, the daring of its coloring, and the grandeur of its setting. Bentivoglio, who was also a diplomat, patron of the arts, and historian, lived in Flanders in the early seventeenth century, but Van Dyck made the portrait in 1623 in Rome, where he likely resided at the cardinal’s palace.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

George Gage with Two Men, ca. 1622–23

Oil on canvas

45 1/4 × 44 3/4 in. (115 × 113.5 cm)

The National Gallery, London

While Van Dyck may already have met the diplomat and artistic agent George Gage in Rubens’s Antwerp studio, the style and setting of the portrait he made of him indicate it was painted in Rome, where Van Dyck and Gage may have befriended each other. Against a dark landscape, two men present a marble sculpture to the Englishman, whose nonchalant pose evokes his worldliness. Gage was indeed involved in the procurement of ancient statuary for English patrons.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Genoese Noblewoman, ca. 1625–27

Oil on canvas

90 7/8 × 61 5/8 in. (230.8 × 156.5 cm)

The Frick Collection; Henry Clay Frick Bequest

Van Dyck spent most of his Italian years in Genoa, a thriving Mediterranean port with an important Flemish community. In the wake of Peter Paul Rubens, who had preceded him there in the first decade of the century, he provided the city’s noble families with grand portraits, many of which still adorn their palaces. This portrait of a luxuriously dressed young woman standing against a loosely defined architectural background is a typical example. Although she remains unidentified, the sash across her torso and the black edges of her cuffs seem to indicate she is a widow.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Standing Woman in a Nun’s Habit (Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia?), ca. 1627

Pen and brown ink on paper

6 3/16 × 4 1/4 in. (15.7 × 10.8 cm)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Helen and Alice Colburn Fund

Throughout his career, Van Dyck used pen to record initial ideas for portraits, but judging from the rare extant examples, these studies increasingly lost the level of detail of the earlier sheets. Instead, they adopt the more modest appearance exemplified by this sketch. The format indicates a woman of aristocratic or high ecclesiastical standing, possibly Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia, daughter of King Philip II of Spain and (with her husband) regent of the Southern Netherlands during the early decades of the century.

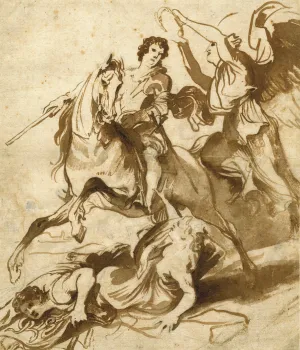

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Portrait Study of a Commander on Horseback Triumphing over Evil, and Crowned by Victory, 1621–ca. 1627

Pen, brush, and brown ink, with brown wash, over black chalk

8 1/2 × 7 1/4 in. (21.5 × 18.4 cm)

The British Museum, London

This drawing records Van Dyck’s most ambitious equestrian portrait, though the painting it probably prepared never seems to have been executed. A young man, wearing armor and a billowing commander’s sash, tramples with his spirited horse the two personifications of evil, one of which is holding a bunch of snakes. The hero is crowned with laurels by the winged figure of Fame, possibly in reference to a specific military victory. The style and flamboyant composition situate the drawing firmly in Van Dyck’s Italian period.