The Iconographie

The Iconographie and Other Early Portrait Prints after Van Dyck

Van Dyck consolidated his reputation as Europe’s foremost portraitist through the publication of prints. His main endeavor in the medium, a series of prints of his portraits known as the Iconographie, reproduced likenesses of some of the most famous crowned heads, military men, scholars, and artists of the time, dating to the first years after his return to Flanders from Italy in 1627. A first edition appeared in 1632, but no copy is preserved, and the genesis and further evolution of the series remains enigmatic. Van Dyck himself etched the first state of some of the prints, in an intuitive graphic style that elevated him to the ranks of the best printmakers of all time. A selection of prints from the series and three additional prints possibly published during Van Dyck’s lifetime are on view in this Cabinet, while the largest group ever assembled of drawings and oil sketches made in preparation for the Iconographie is exhibited downstairs in the South Gallery.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Self-Portrait, ca. 1627–35

Etching (first state)

9 5/8 × 6 1/8 in. (24.4 × 15.6 cm)

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

A masterpiece of seventeenth-century printmaking, Van Dyck’s etched self-portrait is as remarkable for its technique as for its unfinished appearance. The painter’s handsome features float at the top of a sheet that is otherwise empty, save for the light scratches in the copper plate from which it was pulled. The state would not have been considered final by any standard of the time, but it is clear from the surviving impressions that it was marketed and appreciated as an exceptional work of art.

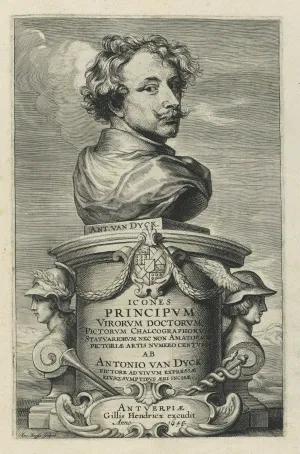

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) and Jacob Neefs (1610–1660)

Anthony van Dyck, ca. 1644

Etching and engraving (third state)

In Icones Principum . . . (Antwerp, 1645 or 1646), bound in gold-stamped seventeenth-century calfskin

Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

For the earliest known edition of the Iconographie, published by Gillis Hendricx in 1645, Van Dyck’s unfinished etched self-portrait was made into a frontispiece by the engraver Jacob Neefs, the head transformed into a marble bust placed on a pedestal and inscribed with the edition’s title (“One Hundred Images of Princes, Scholars, Painters,” etc.). The copy shown here is one of the few preserved in a seventeenth-century binding. The painted portrait that Van Dyck originally intended to make into a print was later engraved by Lucas Vorsterman.

Lucas Vorsterman the Elder (1595/96–1674/75) after Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Anthony van Dyck, ca. 1635

Engraving (fourth state)

9 7/8 × 6 1/4 in. (25.1 × 15.8 cm)

Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, Paris

For the earliest known edition of the Iconographie, published by Gillis Hendricx in 1645, Van Dyck’s unfinished etched self-portrait was made into a frontispiece by the engraver Jacob Neefs, the head transformed into a marble bust placed on a pedestal and inscribed with the edition’s title ("One Hundred Images of Princes, Scholars, Painters," etc.). The copy shown here is one of the few preserved in a seventeenth-century binding. The painted portrait that Van Dyck originally intended to make into a print was later engraved by Lucas Vorsterman.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Hendrick van Balen, 1627–32

Black chalk

9 5/8 × 7 3/4 in. (24.3 × 19.8 cm)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The rolls of the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke for the year 1610 list Van Dyck as an apprentice with the guild’s dean, the painter Hendrick van Balen. Nearly two decades later, Van Dyck focused his attention on his teacher’s craggy face and wispy hair, only roughing out his costume and hands. In a grisaille oil sketch at Boughton House, Van Dyck subsequently fleshed out this composition, clarifying the sculpted head on which Van Balen rests his hand and situating him in front of a column.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, ca. 1627–35

Black chalk

9 5/8 × 7 3/4 in. (24.5 × 19.8 cm)

The Duke of Devonshire and the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, Chatsworth, Derbyshire

The son and namesake of the greatest Netherlandish painter of the sixteenth century, Pieter Brueghel the Younger devoted his career to producing a vast number of copies and variations of his father’s work. Van Dyck made two drawings of Brueghel to prepare a print for the Iconographie series. In the drawing shown here, Brueghel appears in three-quarter profile, turned away from the viewer, clasping his cloak to his chest.

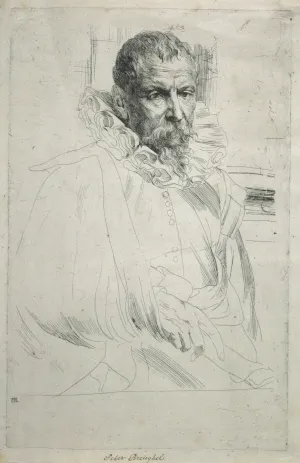

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, ca. 1627–35

Etching (first state)

9 5/8 × 6 1/8 in. (24.4 × 15.6 cm)

Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge; Gift of Walter C. Klein

The son and namesake of the greatest Netherlandish painter of the sixteenth century, Pieter Brueghel the Younger devoted his career to producing a vast number of copies and variations of his father’s work. Van Dyck made two drawings of Brueghel to prepare a print for the Iconographie series. In the drawing shown here, Brueghel appears in three-quarter profile, turned away from the viewer, clasping his cloak to his chest.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Adriaen Brouwer, ca. 1634

Oil on panel

8 1/2 × 6 3/4 in. (21.6 × 17.2 cm)

The Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry KBE, Boughton House, Northamptonshire

The work of the painter Adriaen Brouwer, whose subjects were often drawn from low-life and taverns, was sought after by the most discerning collectors of his time, including Peter Paul Rubens and Rembrandt. Van Dyck’s grisaille was probably made in 1634, when Brouwer was living with Van Dyck’s frequent collaborator, the printmaker Paulus Pontius. It served as the model for an engraving by Schelte Adamsz. Bolswert.

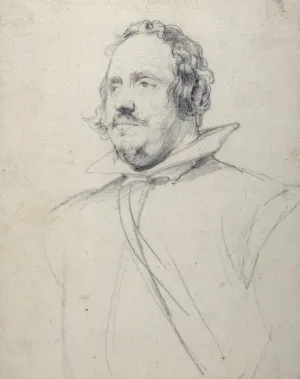

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Gaspar de Crayer, ca. 1627–35

Black chalk

9 5/8 × 7 1/2 in. (24.3 × 19 cm)

The Duke of Devonshire and the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, Chatsworth, Derbyshire

The painter Gaspar de Crayer dominated the market for altarpieces in seventeenth-century Brussels. Van Dyck’s drawing is highly finished, but for his engraving, Paulus Pontius worked instead from an intermediary grisaille, the tonal richness of which could communicate Van Dyck’s intentions better than a chalk drawing. De Crayer holds a portfolio in the drawing, which Pontius reworked as part of the cape slung over the sitter’s right shoulder.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Gaspar de Crayer, ca. 1627–35

Oil on panel

The Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry KBE, Boughton House, Northamptonshire

The painter Gaspar de Crayer dominated the market for altarpieces in seventeenth-century Brussels. Van Dyck’s drawing is highly finished, but for his engraving, Paulus Pontius worked instead from an intermediary grisaille, the tonal richness of which could communicate Van Dyck’s intentions better than a chalk drawing. De Crayer holds a portfolio in the drawing, which Pontius reworked as part of the cape slung over the sitter’s right shoulder.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Manuel Frockas, 1631–32 (?)

Black chalk

9 5/8 × 7 7/8 in.

The Duke of Devonshire and the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, Chatsworth, Derbyshire

Van Dyck’s Iconographie series of prints includes three Spanish generals whose military careers brought them to Flanders, among them, Manuel Frockas, Count of Feria. Simplicity of composition and relatively cursory execution distinguish these generals’ portrait drawings, likely all made from life in 1631–32. While the drawings appear to depict the sitters in civilian dress, the later oil sketches and engravings show them in full armor, each holding a commander’s baton.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Manuel Frockas, 1631–32 (?)

Oil on panel

8 1/4 × 6 1/4 in. (21 × 15.9 cm)

The Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry KBE, Boughton House, Northamptonshire

Van Dyck’s Iconographie series of prints includes three Spanish generals whose military careers brought them to Flanders, among them, Manuel Frockas, Count of Feria. Simplicity of composition and relatively cursory execution distinguish these generals’ portrait drawings, likely all made from life in 1631–32. While the drawings appear to depict the sitters in civilian dress, the later oil sketches and engravings show them in full armor, each holding a commander’s baton.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Orazio Gentileschi, ca. 1635

Black chalk, gray wash, pen and brown ink; incised for transfer

9 3/8 × 7 in. (24 × 17.9 cm)

The British Museum, London

In the early years of the seventeenth century, Orazio Gentileschi worked as a painter in Rome, where he came under the influence of Caravaggio. His career then took him to Turin, Genoa, Paris, and finally the court of Charles I in London, where he was joined by his daughter, Artemisia, also a painter. Van Dyck shows the artist, who was known for his difficult personality, looking out at the viewer in a surly manner. The general composition seems to have been based on Italian prototypes, the work of Titian above all, present in the collections of Charles I in London.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Gaspar Gevaerts, ca. 1627–35

Black chalk, incised for transfer

10 5/8 in. × 7 1/2 in. (27 × 19 cm)

Albertina, Vienna

Better known by his Latinized name Gevartius, Gaspar Gevaerts was a preeminent philologist and historian, serving as secretary of Antwerp for four decades. In the drawing, preparatory to an engraving by Paulus Pontius for the series known as the Iconographie, Van Dyck alludes to Gevaerts’s scholarly endeavors with a single book. He renders the face in exquisite focus while rapidly sketching elements of dress and pose with thicker lines.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Gaspar Gevaerts, ca. 1627–35

Oil on panel

8 1/4 × 6 1/2 in. (24.8 × 18.7 cm)

The Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry KBE, Boughton House, Northamptonshire

Better known by his Latinized name Gevartius, Gaspar Gevaerts was a preeminent philologist and historian, serving as secretary of Antwerp for four decades. In the drawing preparatory to an engraving by Paulus Pontius for the series known as the Iconographie, Van Dyck alludes to Gevaerts’s scholarly endeavors with a single book. He renders the face in exquisite focus while rapidly sketching elements of dress and pose with thicker lines.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Inigo Jones, 1632–36

Black chalk, pen and brown ink; squared for transfer in black chalk

9 5/8 × 7 7/8 in. (24.4 × 20.1 cm)

The Duke of Devonshire and the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, Chatsworth, Derbyshire

Inigo Jones worked as a theatrical designer throughout the reigns of James I and Charles I while also assuming the role of Surveyor of the King’s Works in 1615. The projects he carried out while in this capacity, including the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace and the piazza at Covent Garden, furthered Jones’s introduction of a Palladian classicism to English architecture. In this drawing, likely not made from life but based by Van Dyck on an earlier portrait, Jones appears behind a parapet, holding a sheet of paper in an allusion to his gifts as a draftsman.

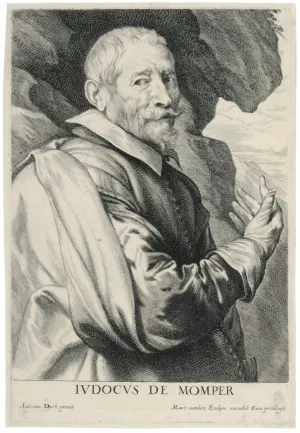

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Joos de Momper the Younger, ca. 1627–35

Etching (first state)

9 5/8 × 6 1/8 in. (24.4 × 15.6 cm)

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The painter Joos de Momper specialized in mountainous landscapes. In the portrait at right, Van Dyck’s etching technique — consisting of stippling, lines alternatingly scratchy or fluent, and areas of dense hatching — conveys the varied textures of the wrinkled skin, curly hair, leather glove, and rugged landscape. Probably to preserve Van Dyck’s original, the plate was not finished with the burin in later states, but a completely new print was made by the engraver Lucas Vorsterman.

Lucas Vorsterman the Elder (1595/96–1674/75) after Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Joos de Momper the Younger, ca. 1627–35

Etching and engraving (third state)

9 × 6 1/8 in. (23 × 15.6 cm)

Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, Paris

The painter Joos de Momper specialized in mountainous landscapes. In the portrait at right, Van Dyck’s etching technique — consisting of stippling, lines alternatingly scratchy or fluent, and areas of dense hatching — conveys the varied textures of the wrinkled skin, curly hair, leather glove, and rugged landscape. Probably to preserve Van Dyck’s original, the plate was not finished with the burin in later states, but a completely new print was made by the engraver Lucas Vorsterman.

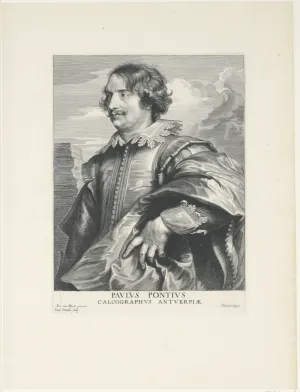

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) and an Unidentified Engraver

Paulus Pontius, ca. 1627–30

Etching (second state)

9 1/8 × 7 1/4 in. (23.3 × 18.3 cm

Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Van Dyck’s most fully worked-out etching depicts one of his main engravers with the costume and swagger of a gentleman. In this second state of the print, an unidentified engraver added hatching in the background, but Van Dyck’s masterful graphic treatment of the subject — despite scratches in the plate and other small technical accidents — can still be fully appreciated.

Paulus Pontius (1603–1658) after Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Paulus Pontius, ca. 1627–35

Engraving (fifth state)

9 5/8 × 7 1/8 in. (24.6 × 18.2 cm)

Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, Paris

Paulus Pontius was a prolific engraver whose collaboration with Peter Paul Rubens, Van Dyck, and other artists resulted in some of the best engravings published in seventeenth-century Flanders. He contributed more plates to Van Dyck’s Iconographie than any other printmaker. Probably made a few years after an earlier portrait, of which a largely etched state is also on view in this gallery, this completely engraved print differs not only in the more established appearance of the sitter but also in the smooth finish.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Jan van Ravesteyn, 1628–29 or 1632

Black chalk

10 × 7 7/8 in. (25.3 × 20.1 cm)

Albertina, Vienna

Jan van Ravesteyn was a portrait painter active in The Hague, and Van Dyck likely drew him when he was there working on important commissions from stadholder Frederick Henry. Van Dyck’s sympathetic portrait depicts Van Ravesteyn, who was around sixty, with great dignity. The artist probably worked from life, using a sharp piece of chalk that allowed for sufficient detail to draw the head and the intricate patterns formed by the layers of the linen ruff, while the outline of Van Ravesteyn’s body is indicated more broadly.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Nicolaas Rockox, ca. 1627–35

Black chalk

11 3/4 × 8 1/2 in. (30.2 × 21.7 cm)

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Royal Collection, Windsor

This drawing, almost certainly made from life, provided the prototype for Van Dyck’s grisaille of Nicolaas Rockox, the Antwerp mayor who was an important patron of the artist. It accords with one characteristic type of portrait sketch in Van Dyck’s oeuvre: entirely in black chalk, with a detailed rendering of physiognomy and rougher indications of dress and attributes. Rockox’s left hand rests on a large sculpted head, probably representing Minerva, goddess of wisdom. With his right hand, he points straight at her forehead.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Nicolaas Rockox, 1636

Oil on panel

diam. 6 in. (15.2 cm)

Collection Howard and Nancy Marks

Unlike the other grisailles, Van Dyck’s portrait of Nicolaas Rockox, a towering figure in the political and cultural life of Antwerp, has an unusual round format. It was likely painted for Rockox’s own collection and reflected his interest in ancient coins. Paulus Pontius’s engraving meanwhile embellishes the portrait with an architectural framework and Latin verses by Gaspar Gevaerts that praise Rockox for his unwavering service and indifference to power.

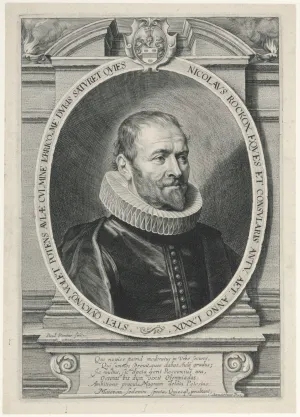

Paulus Pontius (1603–1658) after Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Nicolaas Rockox, 1639

Engraving (first state)

10 1/2 × 7 1/8 in. (26.7 × 18.2 cm)

Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, Paris

Unlike the other grisailles shown here, Van Dyck’s portrait of Nicolaas Rockox, a towering figure in the political and cultural life of Antwerp, has an unusual round format. It was likely painted for Rockox’s own collection and reflected his interest in ancient coins. Paulus Pontius’s engraving meanwhile embellishes the portrait with an architectural framework and Latin verses by Gaspar Gevaerts that praise Rockox for his unwavering service and indifference to power.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Frans Snyders, ca. 1627–35

Etching (first state)

9 5/8 × 6 1/8 in. (24.4 × 15.6 cm)

Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge; Gift of Walter C. Klein, Class of 1939

As in his own self-portrait, Van Dyck etched only the head of the still-life painter Frans Snyders in this print, basing it on the portrait in The Frick Collection. It may be the only plate in Van Dyck’s Iconographie series for which it can be shown that the painting preceded the print by several years. More than the print’s final version, finished with the burin by the engraver Jacob Neefs, the etched state brings out the aloof distinction with which Van Dyck depicted his colleague.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Hendrick van Steenwijck the Younger, ca. 1632−38

Black chalk, gray wash; incised for transfer

10 3/4 × 8 1/4 in. (27.2 × 20.9 cm)

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

This depiction of Hendrick van Steenwijck the Younger, a painter of imaginary architectural views, is one of Van Dyck’s most accomplished portrait drawings. Deep shadows enhance the sitter’s strong features, long curls and facial hair, the nervous line of the lace ruffs around his wrists, and the strong gestures of his hands. Although blank, both in the drawing and in Paulus Pontius’s faithful engraving after it, the sheet of paper must refer to Van Steenwijck’s mastery as a perspectival draftsman.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Lucas Vorsterman, ca. 1631 (?)

Black chalk

9 3/4 × 7 in. (24.4 × 17.9 cm)

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Van Dyck’s brooding portrait of the engraver Lucas Vorsterman has colored the latter’s reputation, along with anecdotal evidence for his instability, aggression, and hostile relationship with Peter Paul Rubens. Van Dyck knew Vorsterman well from the period when both were working under Rubens’s supervision, and he may have learned how to etch from him. In his autograph print, Van Dyck amplified the nervous energy of his chalk drawing. A second portrait of Vorsterman engraved after Van Dyck is displayed here.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Lucas Vorsterman, ca. 1631 (?)

Etching (first state)

15 3/4 × 10 3/4 in. (40.1 × 27.2 cm)

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Van Dyck’s brooding portrait of the engraver Lucas Vorsterman has colored the latter’s reputation, along with anecdotal evidence for his instability, aggression, and hostile relationship with Peter Paul Rubens. Van Dyck knew Vorsterman well from the period when both were working under Rubens’s supervision, and he may have learned how to etch from him. In his autograph print, Van Dyck amplified the nervous energy of his chalk drawing. A second portrait of Vorsterman engraved after Van Dyck is on view in the Cabinet.

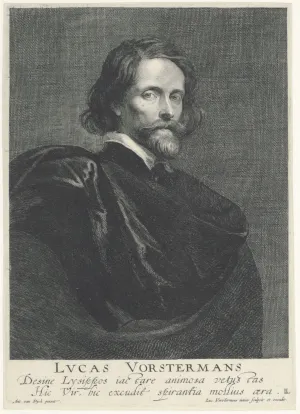

Lucas Vorsterman the Younger (1624–1666 or later) after Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Lucas Vorsterman the Elder, ca. 1650 (?)

Engraving (fourth state)

9 7/8 × 7 in. (25 × 17.8 cm)

Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, Paris

Lucas Vorsterman was a major figure in seventeenth-century Flemish art, both as a printmaker and as a publisher. His close collaboration with Peter Paul Rubens ended when the two artists fell out, opening the way for Vorsterman to pursue independent success. The present print, made by the engraver’s son after an unknown model by Van Dyck, captures the complex and haughty nature of its subject. An etched portrait of Vorsterman by Van Dyck is also known, of which an impression is exhibited downstairs, together with the drawing that served as its model.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Sebastiaan Vrancx, ca. 1628–31

Black chalk

10 1/16 × 7 3/8 in. (25.6 × 18.7 cm)

The British Museum, London

Mainly known for his small landscape paintings and drawings featuring battles and robberies, Sebastiaan Vrancx was also a book illustrator, poet, playwright, and member of Antwerp’s militia. Van Dyck’s drawing of Vrancx appears to have been made from life: apart from his face and right sleeve, the draftsmanship is not very detailed. In a gesture toward Vrancx’s military duties, his right hand emphasizes his sword, of which only the summarily indicated hilt is visible.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Jan Wildens, ca. 1627–32

Black chalk, light and dark gray and brown washes; incised for transfer

9 1/8 × 7 7/8 in. (23.3 × 20 cm)

The British Museum, London

The painter Jan Wildens, who was also active as an art dealer, specialized in wooded landscapes. He is known for collaborating on the backgrounds of other artists’ works, notably those of Peter Paul Rubens and possibly Van Dyck as well. In this drawing, the initial sketch in black chalk is finished with large areas of wash in order to model the figure. The outlines are incised for transfer onto the copper plate, which was engraved by Paulus Pontius, likely without the mediation of a grisaille on panel.

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), with additional etching and engraving attributed to Lucas Vorsterman the Elder (1595/96–1674/75)

Jan van den Wouwer, 1632 (?)

Etching and engraving (second state)

9 3/4 × 6 1/4 in. (24.9 × 15.8 cm)

Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Van Dyck must have met the distinguished lawyer and philologist Jan van den Wouwer in Peter Paul Rubens’s circle and may have portrayed him before leaving for Italy in 1621. A later painting (Pushkin Museum, Moscow), in which Van den Wouwer wears a cloak trimmed with leopard skin and a golden chain, was the basis for this print. Its first, purely etched state is believed to be by Van Dyck. In the second state, shown here, an engraver, possibly Lucas Vorsterman, modeled the face more thoroughly with fine burin lines, refining the print with a wonderful luster.

Paulus Pontius (1603–1658) after Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Stadholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, ca. 1638 (?)

Engraving (third state)

19 × 13 1/2 in. (48.3 × 34.2 cm)

Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, Paris

Fredrick Henry, Prince of Orange and stadholder of the Dutch Republic between 1625 and 1647, became an important patron of Van Dyck’s after the artist’s return from Italy in 1628. The history paintings he commissioned speak to his ambition to raise the artistic prestige of his court, and the portraits were the first Van Dyck made for a head of state and his family. Here, Paulus Pontius’s polished engraving technique skillfully translates the tone and color of Van Dyck’s painted portrait of Frederick Henry.

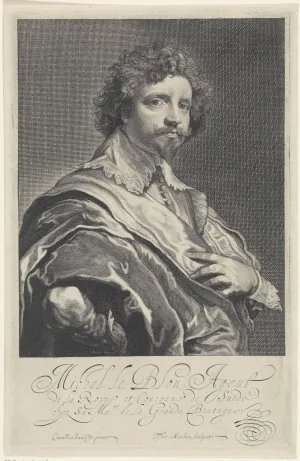

Theodor Matham (1605–1676) after Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Michiel le Blon, 1632–54

Engraving (sixth state)

11 3/8 × 7 5/16 in. (28.9 × 18.6 cm)

Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Michiel le Blon’s combined careers as a diplomat and art dealer brought him to the Netherlands, Flanders, Italy, England, and Sweden. Among other transactions, he was involved in major sales from the collections of Peter Paul Rubens and (after his death) Van Dyck. Probably commissioned by Le Blon himself, perhaps as a kind of calling card, this portrait was made by the outstanding Dutch engraver Theodor Matham after a painting by Van Dyck from around 1630. The calligraphic French inscription describes Le Blon as "agent of the Queen and Crown of Sweden."