Complete Checklist

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Three Studies of Resting Soldiers (recto), ca. 1713–14

Verso: A Group of Actors

Red chalk

6 7/8 × 8 9/16 in. (17.5 x 21.7 cm)

École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris

Watteau’s drawings are notable for the way they capture the interiority of their subjects, often by focusing on states of repose. The men here, probably drawn from the same model, are immersed in a world of private experience, enjoying a moment of tranquility that defies the dehumanizing conditions of war.

Philips Wouwerman (1619–1668)

The Cavalry Camp, 1638–68

Oil on oak panel

16 3/4 x 20 3/4 in. (42.5 x 52.7 cm)

The Frick Collection; Henry Clay Frick Bequest

Paintings by the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Philips Wouwerman, a specialist in military camp scenes, were much sought after in early eighteenth-century Paris, and Watteau’s military works owe a clear debt to them. Like most of Wouwerman’s camp scenes, this painting offers a placid, picturesque image of war in which compositional unity reinforces a vision of social harmony.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Studies of Foot Soldiers, a Drummer, and Two Cavaliers (verso),

ca. 1709–10

Red chalk

6 5/16 × 7 11/16 in. (16 x 19.5 cm)

National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh; Accepted by HM Government in Lieu of Inheritance Tax and allocated to The National Gallery of Scotland, 2010

This is one of Watteau’s earliest studies of soldiers. It is less technically sure than his later drawings, but his interest in the mundane aspects of military life is already evident. The marching soldiers face slightly different directions, each encapsulating an individual encounter between artist and model. None of the figures exactly matches those in any known painting.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Studies of a Seated Man with Drawing Portfolio and Standing Man, ca. 1710

Red chalk, within brown ink framing lines

4 7/8 x 3 5/8 in. (12.4 x 9.2 cm)

Private collection

Neither man here is recognizably a soldier — in fact, the seated man is an artist. But Watteau used the standing figure, adding a tricorne hat, in his Bivouac (ca. 1710), now in Moscow at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Two Studies of Standing Soldiers, ca. 1710

Red chalk on aged-toned paper, within black ink framing lines

5 5/8 x 3 1/8 in. (14.3 x 8 cm)

Collection Professor Donald Stone, New York; Promised gift to the National Gallery of Art, Washington

The figure on the left appears as the central figure in Halt of a Detachment, an engraving of which is in this exhibition.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

The Line of March, ca. 1710

Oil on canvas (originally in oval frame and later extended)

15 3/8 x 19 5/16 in. (39 x 49 cm)

York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery); Presented by F. D. Lycett Green through The Art Fund, 1955

This painting, which has darkened considerably over time, is one of Watteau’s earliest military scenes. Unlike the others, which focus on moments between the fighting, it shows a battle scene, with cannon fire dimly perceptible on the horizon. The main interest of the painting, however, is the encounter in the foreground: an officer thrusts his saber at a seated soldier as his female companion, possibly a prostitute, recoils and two soldiers on the other side of the composition look on calmly.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

The Halt, ca. 1710

Oil on canvas (originally in oval frame and later extended)

12 5/8 x 16 3/4 in. (32 x 42.5 cm)

Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

This tightly packed scene shows soldiers and their hangers-on resting and socializing in a military camp. Various groups are spread out somewhat haphazardly across a stage-like terrain, which is anchored by a towering tree. The composition’s disunity makes the figures stand out individually, focusing our attention on their various interactions as they trade glances across the space of the picture. The poignancy of the painting derives from the way these looks do not seem entirely reciprocated, leaving the status of their relationships unresolved.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Three Studies of a Soldier and a Kneeling Man, ca. 1710

Red chalk, within brown ink framing lines

4 13/16 × 7 11/16 in. (12.2 x 19.5 cm)

École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris

Watteau used the figures in this drawing in two other works in the exhibition: the two central figures appear, in reverse order, in Halt of a Detachment, and all four figures appear in The Halt. Though the three figures on the right were likely based on the same model, the way Watteau disposes the men on the page is suggestive, especially the exchange of glances between the kneeling man and the seated soldier with a musket.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Four Studies of Women, Alternately Standing and Seated, ca. 1710

Red chalk

5 1/4 x 8 in. (13.4 x 20.3)

Indianapolis Museum of Art; The Clowes Collection

Whether wives, mistresses, or prostitutes, women were not an uncommon sight in early modern military camps. Watteau used the seated woman with a veil, whose elegant demeanor would seem more suitable for a fête galante, in The Halt.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Three Studies of Soldiers Holding Muskets and Wearing Capes,

ca. 1710

Red chalk and stump on cream paper, within black ink framing lines

5 11/16 × 8 1/16 in. (14.5 x 20.4 cm)

The Courtauld Institute Galleries, London

Watteau used the soldier in the middle in The Portal of Valenciennes. This is the only surviving drawing in a known location related to the painting, and the two works are shown together for the first time.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

The Portal of Valenciennes, ca. 1710–11

Oil on canvas (originally in oval frame and later extended)

12 3/4 x 16 in. (32.5 x 40.5 cm) Framed: 18 11/16 × 21 5/8 in. (47.5 × 54.9 cm)

The Frick Collection, New York; Purchased with funds from the bequest of Arthemise Redpath, 1991

Watteau’s only known guard scene (as opposed to a march or camp scene), this is one of his best preserved paintings of military life. Suffused with golden light, two pairs of soldiers converse across the space of the picture, while the three other figures in the foreground have withdrawn into sleep or reverie. The enigmatic exchanges among these men transform an otherwise prosaic moment into a moving image of the social conditions of military life and the fragility of human connection.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Two Studies of a Soldier, One Kneeling, the Other Lying Down,

ca. 1710

Red chalk, within black ink framing lines

5 1/8 x 6 in. (13 x 15.3 cm)

Private collection

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Two Studies of a Soldier, One Seated, the Other Standing, ca. 1712

Red chalk, within brown ink framing lines

5 9/16 × 5 7/16 in. (14.2 x 13.8 cm)

Musée du Louvre, Department of Prints and Drawings, Paris

This drawing and Two Studies of a Soldier Viewed from Behind seem to depict the same model and may have been executed during a single session.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Two Studies of a Soldier Viewed from Behind, ca. 1712

Red chalk, within brown ink framing lines

6 5/16 x 6 1/8 in. (16.1 x 15.6 cm)

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven; Everett V. Meeks, B.A. 1901, Fund

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Three Studies of a Military Drummer, ca. 1713

Red chalk on cream paper, within brown ink framing lines, laid down on off-white card

6 1/8 × 7 11/16 in. (15.5 x 19.6 cm)

Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge; Gift of John S. Newberry

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Three Studies of a Soldier, One from Behind, ca. 1713–15

Red chalk, within black ink framing lines

5 15/16 × 7 13/16 in. (15.1 x 19.9 cm)

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

This vigorous drawing is one of a series of studies, perhaps drawn in a single sitting, showing soldiers in three poses arranged in a semicircle. Here, as in the other related studies, the soldiers are positioned to suggest a sequence of movement in time and space. The figure on the far right was also used in Recruits Going to Join the Regiment.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

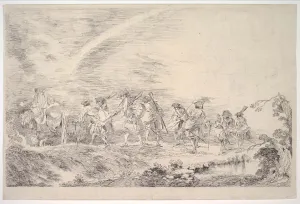

Recruits Going to Join the Regiment, ca. 1715

Etching with dry point, first state of three

8 7/8 × 13 7/16 in. (22.6 x 34.2 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Purchase; Gift of Dr. Mortimer Sackler, Theresa Sackler and Family, and The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2006

Executed with a nervous, almost electric line, this scene of marching soldiers is a rare etching by Watteau after a now-lost painting. Watteau constructed the composition out of a series of studies (two of which are on view on either side of the etching) showing a soldier in three poses. He extracted individual figures and combined them in pairs along a graceful arabesque.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Three Views of a Soldier, One from Behind, ca. 1713–15

Red chalk, within black ink framing lines

6 11/16 x 8 5/8 in. (17 x 21.9 cm)

Musée du Louvre, Department of Prints and Drawings, Paris

Part of Watteau’s series of studies of three soldiers in movement, this drawing is notable for the exaggerated elegance of the figures’ poses. The men here are similar to those in Recruits Going to Join the Regiment, but none match exactly.

Jean-Antoine (1684–1721)

The Supply Train, ca. 1715

Oil on panel (about 21⁄2 in. of landscape cut off right side of original by 1756)

11 1/8 x 12 3/8 in. (28.2 x 31.4 cm)

Collection Lionel and Ariane Sauvage

This painting, which, like most of Watteau’s paintings, has darkened and abraded with age, is probably one of Watteau’s last military works. Formerly in the collection of Cardinal Luigi Valenti Gonzaga (1725–1808), a celebrated eighteenth-century art collector, it was only recently rediscovered. The disordered composition conveys something of the aimlessness of camp life, yet, as always, Watteau’s detached approach carries no moral judgment about war or its participants.

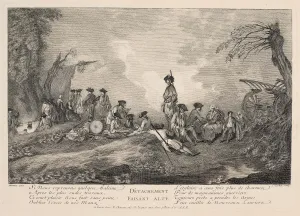

Charles-Nicolas Cochin (1715–1790)

After Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Halt of a Detachment

Engraving

In LŒuvre d’Antoine Watteau, Peintre du Roy en son Académie Roïale de Peinture et Sculpture, gravé d’après ses tableaux et desseins originaux tirez du cabinet du Roy et des plus curieux de l’Europe par les soins de M. de Jullienne, vol. 2. Paris, ca. 1740.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert N. Straus, 1928

Watteau became one of the eighteenth century’s most celebrated artists in part through the dealer Jean de Jullienne’s efforts to have his entire oeuvre, both drawings and paintings, engraved shortly after his death. This engraving, after a now lost painting, is notable for the graceful arabesque of figures spread across the landscape.

Jean Audran (1667–1756)

After Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Two Soldiers

Etching

Overall: 25 3/16 × 19 1/2 × 1 15/16 in. (64 × 49.5 × 4.9 cm)*

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928

These soldiers are etched after two figures in the series of studies related to Recruits Going to Join the Regiment, on view in the exhibition. The soldier on the left comes from Three Studies of a Soldier from Behind, now in Berlin, and the other is taken from Three Views of a Soldier, One from Behind, which is in the exhibition.

Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater (1695–1736)

Standing Soldier with a Pipe, ca. 1725–30

Red chalk

7 3/8 × 3 5/8 in. (18.7 × 9.2 cm)

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

Pater was one of Watteau’s most important followers and, like his master, produced a number of military scenes in addition to fêtes galantes. This study of a soldier, cut from a larger sheet and preparatory for the painting Troops at Rest (Metropolitan Museum of Art), lacks the sense of corporeality that animates Watteau’s drawings but has its own elastic energy.

Nicolas Lancret (1690–1743)

Military Camp, ca. 1722

Oil on panel

6 7/8 × 8 11/16 in. (17.5 x 22 cm)

Collection Dr. Mary Tavener Holmes

Along with Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater, Lancret was Watteau’s other great follower, and his military scenes are near pastiches of his master’s. Many of the figures in this painting are copies after Watteau’s or else closely derive from them. Yet, unlike Watteau, Lancret deploys his figures to generate charming compositional arrangements rather than interpersonal encounters with social and psychological complexity.