Checklist

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Self-Portrait, ca. 1650–55

Oil on canvas

42 1/8 x 30 1/2 in. (107 x 77.5 cm)

The Frick Collection; Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Henry Clay Frick II, 2014

© The Frick Collection

Painted when he was in his mid-thirties, Murillo’s first self-portrait shows him as an upper-class Spaniard, sporting an elegant black outfit with a golilla (a stiff white collar, typical of Spanish fashion). It was probably a private work, painted for his own family. The image of the artist is set in a fictive stone block, chipped and battered by time, that rests on a stone ledge in a realistic manner.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Self-Portrait, ca. 1670

Oil on canvas

48 × 42 1/8 in. (122 × 107 cm)

The National Gallery, London; Bought, 1953

© The National Gallery, London

In this self-portrait, Murillo appears older, forlorn and weary. The painter was, at this point, a widower in his fifties with four children. The canvas is dedicated, in a Latin inscription, to his sons: “Bartolomé Murillo portraying himself to fulfill the wishes and prayers of his children.” To the left of the stone frame is a sheet of paper with a red chalk drawing, a wooden ruler, a compass, and a red chalkholder. On the opposite side are the painter’s brushes and palette.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Juan Arias de Saavedra, 1650

Oil on canvas

53 1/8 × 38 5/8 in. (135 × 98 cm)

Collection Duchess of Cardona

Murillo’s earliest dated portrait, this newly discovered canvas depicts Juan Arias de Saavedra y Ramírez de Arellano (1621–1687), an aristocrat from Seville and a patron of the painter. Both the red cross on his left shoulder and the pendant with a scallop shell refer to his position as a knight in the Order of Santiago. The fictive stone frame includes the sitter’s coat of arms and two putti holding tablets. The one on the left records his age (twenty-nine), while the one on the right has the date on which the portrait was painted (1650).

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Young Man, 1650–55

Oil on canvas

25 3/8 × 17 3/4 in. (64.4 × 45.2 cm)

Private collection

This charming portrait of an unknown young man first appeared on the market in 2009, as an anonymous Spanish work. By comparison with Murillo’s portrait of Juan Arias de Saavedra and the Frick self-portrait, it can be attributed to the painter and dated to the first half of the 1650s. It is tempting to identify the sitter as one of the painter’s sons, but he is more likely an aristocrat from Seville. The painting was cut down on all sides at an unknown date.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Standing Male Figure: Study for a Portrait, ca. 1660

Pen and brown ink over traces of black chalk underdrawing on off-white paper

5 5/8 × 4 in. (14.3 × 10.2 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1965

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Beginning in the 1650s, Murillo painted a series of full-length portraits. After a trip to Madrid in 1658, he was profoundly influenced by the art of Titian, Rubens, Van Dyck, and Velázquez, whose work he admired in the royal collection in the capital. Only five drawings for portraits by Murillo have been identified. This one must be connected to a painting that was either never executed or is lost. Drawings such as this were used by the artist to plan an overall composition and possibly also to seek approval from patrons.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Nicolás Omazur, 1672

Oil on canvas

32 5/8 × 28 3/4 in. (83 × 73 cm)

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

© Museo Nacional del Prado

A merchant from Antwerp who moved to Seville in the late 1660s, Nicolás Omazur (ca. 1630–1698) owned more than two hundred paintings, including thirty-one by Murillo, who was a close friend. This painting has a pendant portrait of Omazur’s wife, Elizabeth Maelcamp (now in a private collection). The top part of a fictive stone cartouche is barely visible at the bottom of the canvas. Descriptions in seventeenth-century inventories establish that the painting has been substantially cut down.

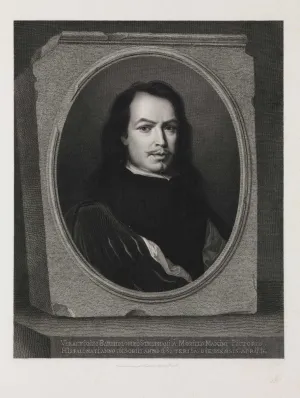

Richard Collin, after Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, 1682

Engraving on paper

13 3/4 × 9 1/4 in. (35 × 23.5 cm)

Private collection, New York

Photo Michael Bodycomb

Closely based on Murillo’s London self-portrait, this ambitious engraving was the first to disseminate Murillo's image across Europe. It was commissioned by his friend and patron Nicolás Omazur and was signed and dated by Richard Collin, royal engraver to King Charles II of Spain. Collin lived in Brussels after 1678 and must have used a drawing after the self-portrait, presumably sent from Seville to Flanders, to create the print. Executed soon after Murillo’s death, the engraving was intended to memorialize the painter.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Two Women at a Window, ca. 1655–60

Oil on canvas

49 1/4 × 41 1/8 in. (125.1 × 104.5 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington; Widener Collection

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Deeply interested in the boundaries between art and reality, Murillo used trompe l’oeil solutions in his self-portraits to play with the pictorial space of his compositions. This exceptionally realistic painting, one of Murillo’s most famous and mysterious works, is devised as the space of a window. Emerging from the darkness are two young girls who may be prostitutes. The painting may refer to a Spanish proverb: "la mujer ventanera, uva de la calle" (a woman at the window, a grape of the street).

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

A Peasant Boy Leaning on a Sill, ca. 1675

Oil on canvas

20 1/2 × 15 1/8 in. (52 × 38.5 cm)

The National Gallery, London; Presented by M.M. Zachary, 1826

© The National Gallery, London

The vivid representation of this jovial boy is related to Murillo’s representation of street urchins in larger canvases. The boy is shown at a window, which implies a space beyond the pictorial realm. It was originally intended to respond to a second painting, Young Girl Lifting Her Veil (in a private collection), with the gaze of the boy directed toward the beautiful image of the girl. The message would have been apparent when they were shown together on the same wall.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Diego Ortiz de Zúñiga, ca. 1655

Oil on canvas

44 1/2 x 37 in. (113 x 94 cm)

Private collection, United Kingdom

Image Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Long believed to be a copy after a lost Murillo (and described as such in the exhibition catalogue), this portrait has very recently been restored and discovered to be the original. A celebrated aristocrat in Seville, Diego Ortiz de Zúñiga (1633–1680) was also a historian who charted the history of the city from the Middle Ages to 1671 in his Annales eclesiásticos y seculares de la ciudad de Sevilla. His coat of arms appears at the top of the frame and the cross of the Order of Santiago on his left shoulder.

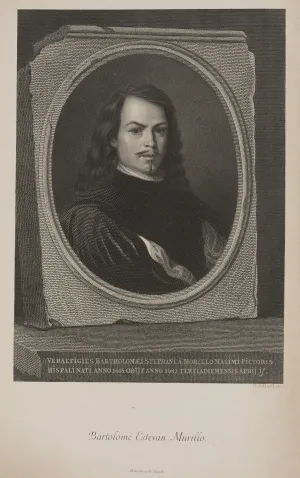

Manuel Alegre, after Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, 1790

Engraving and etching on paper

12 5/8 × 8 5/8 in. (32 × 22 cm)

Fundación Fondo de Cultura de Sevilla (Focus), Seville

This print — the first known after the Frick self-portrait — was produced in 1790 in Madrid, by Manuel Alegre. At the time, the painting was in the collection of Bernardo de Iriarte, a prominent political and cultural figure in the Spanish capital. Iriarte was the Vice-Protector of the Academia of San Fernando, and Alegre states in the inscription that he was awarded a prize by the academy for this engraving. Iriarte had lent the portrait to the academy so that students could copy it.

Manuel Alegre, after Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, 1790

Graphite and brown ink on paper

9 7/8 × 7 3/8 in. (25 × 18.8 cm)

Fundación Fondo de Cultura de Sevilla (Focus), Seville; Legado Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez

This drawing is closely related to the 1790 engraving after Murillo’s self-portrait by Manuel Alegre. Executed in graphite and brown ink, it is the same size as the print and is likely a proof made by Alegre to see how the image and text worked together before he printed the full image with the additional texts.

Auguste Blanchard fils âiné, after Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, ca. 1842

Etching and engraving on paper

15 × 11 in. (38 × 28 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Mrs John H. Wright, 1946

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Between 1838 and 1849, Murillo’s self-portrait was displayed to the public as a prominent part of King Louis Philippe d’Orleáns’s collection of Spanish paintings — the so-called Galerie Espagnole — at the Louvre in Paris. This large print was produced after the painting arrived in Paris and attests to its celebrity in France at the time.

Paulus Pontius, after Diego Velázquez and Peter Paul Rubens

Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares, ca. 1626

Engraving on paper

23 3/4 × 17 1/8 in. (60.3 × 43.6 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington; Gift of the Estate of Leo Steinberg, 2011

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

Northern prints such as this provided the visual model for many of Murillo’s portraits and their framing devices. The portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares, King Philip IV’s minister and one of the most powerful men in Spain, is based on an image by Velázquez, while the framing elements were designed by Rubens. Palm branches, torches, and trumpets herald the sitter’s fame. The spear, shield, and owl of Minerva (on the left) praise his wisdom, while the club and lion skin of Hercules (on the right), celebrate his strength.

Henry Adlard, after Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

From William Stirling-Maxwell, Annals of the Artists of Spain (London, 1848)

Steel engraving on paper

5 7/8 × 4 1/4 in. (14.8 × 10.7 cm)

The National Gallery, London, Libraries and Archives Department

© The National Gallery, London

As the discipline of art history became better codified in the nineteenth century, books on Spanish art, and on Murillo in particular, began to be published. The four volumes in the exhibition demonstrate how Murillo’s self-portrait at the Frick had become the standard image of the painter in the art historical literature of the period. Before photography became an indispensable tool for art history, these engravings faithfully reproduced the original painting, which at that time moved between different collections in Paris and London.

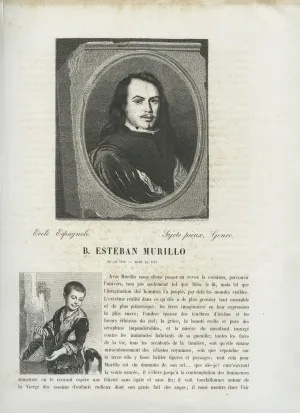

Jean-Baptiste-Charles Carbonneau, after Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

From Charles Blanc, Histoire des peintres de toutes les Ecoles (Paris, 1869)

Engraving on paper

5 1/8 × 4 3/8 in. (13 x 11 cm)

Private collection, New York

Photo Michael Bodycomb

As the discipline of art history became better codified in the nineteenth century, books on Spanish art, and on Murillo in particular, began to be published. The four volumes in the exhibition demonstrate how Murillo’s self-portrait at the Frick had become the standard image of the painter in the art historical literature of the period. Before photography became an indispensable tool for art history, these engravings faithfully reproduced the original painting, which at that time moved between different collections in Paris and London.

Murillo's Self-Portrait

From Ellen Minor, Murillo (London, 1882)

Engraving on paper

5 1/8 × 4 1/8 in. (12.9 x10.4 cm)

Private collection, New York

Photo Michael Bodycomb

As the discipline of art history became better codified in the nineteenth century, books on Spanish art, and on Murillo in particular, began to be published. The four volumes in the exhibition demonstrate how Murillo’s self-portrait at the Frick had become the standard image of the painter in the art historical literature of the period. Before photography became an indispensable tool for art history, these engravings faithfully reproduced the original painting, which at that time moved between different collections in Paris and London.

Murillo's Self-Portrait

From Albert F. Calvert, Murillo: A Biography and Appreciation (London, 1907)

Engraving on paper

4 1/2 × 3 1/4 in. (11.3 x 8.1 cm)

Private collection, New York

Photo Michael Bodycomb

As the discipline of art history became better codified in the nineteenth century, books on Spanish art, and on Murillo in particular, began to be published. The four volumes in the exhibition demonstrate how Murillo’s self-portrait at the Frick had become the standard image of the painter in the art historical literature of the period. Before photography became an indispensable tool for art history, these engravings faithfully reproduced the original painting, which at that time moved between different collections in Paris and London.