Checklist

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Gentleman in Adoration before the Madonna and Child, ca. 1555

Oil on canvas

23 1/2 x 25 1/2 in. (59.7 x 64.8 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection (1939.1.114)

Courtesy National Gallery of Art Washington

Derived from the tradition of the donor portrait, the sacred portrait is a genre invented by Moroni. The artist’s three surviving sacred portraits (one shown here, Gentleman in Contemplation of the Baptism of Christ, and Two Donors in Adoration before the Madonna and Child and St. Michael) are in this exhibition united for the first time. In all three, portraits of contemporary sitters who appear to pray to, or before, sacred figures dominate the composition.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

Virgin and Child on a Crescent Moon with a Starry Crown and Scepter, dated 1516

Engraving

4 9/16 x 2 15/16 in. (11.6 x 7.4 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Fletcher Fund, 1919 (19.73.39)

Moroni derived the sacred figures in the Gentleman in Contemplation before the Madonna and Child from this popular devotional print, one of four versions produced by Dürer. Why Moroni chose this model is unknown; perhaps the portrait’s sitter owned an impression of it. Transforming Dürer’s image into a more austere yet more intimate depiction of the mother and child, Moroni eliminated the Virgin’s ornate crown and scepter, presenting instead the Christ Child clutching her finger.

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Gentleman in Contemplation of the Baptism of Christ, mid-1550s

Oil on canvas

41 x 44 1/2 in. (104 x 113 cm)

Etro Collection

As in Moroni’s two other surviving sacred portraits, (Gentleman in Adoration before the Madonna and Child, and Two Donors in Adoration before the Madonna and Child and St. Michael) the unidentified sitter appears to have been studied from life while the sacred scene beyond him is stylized. Why the sitter chose to be associated with St. John the Baptist is unknown; the saint may have been his namesake (“Giovanni Battista”).

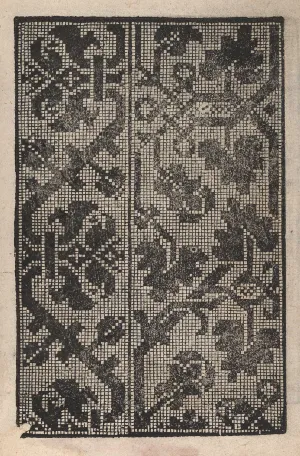

Matteo Pagano (1515–1588)

Ornamento delle Belle & Virtuose Donne

Venice: Matteo Pagano, 1554

Woodcut

7 1/2 x 5 7/8 in. (19 x 15 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1921 (21.15.2bis)

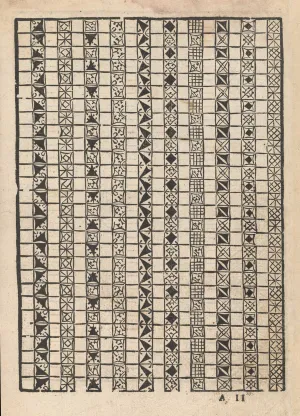

Matteo Pagano (1515–1588)

Giardineto Novo di Punti Tagliati et Gropposi per Exercitio & Ornamento delle Donne

Venice: Matteo Pagano, 1554

Woodcut

7 5/8 x 6 3/8 in. (19.4 x 16.2 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Rogers Fund, 1921 (21.15.1bis )

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Two Donors in Adoration before the Madonna and Child and St. Michael, ca. 1557–60

Oil on canvas

35 1/4 x 38 1/2 in. (89.5 x 97.8 cm)

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond; Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund (62.20)

© Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond / Katherine Wetzel

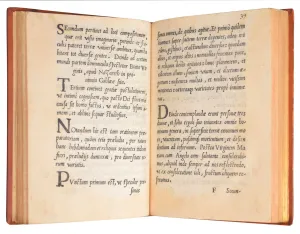

St. Ignatius of Loyola

Exercitia Spiritualia

Rome: Apud Antonium Bladum, 1548

6 1/8 x 4 3/8 in. (15.5 x 11 cm)

Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (49043050)

Moroni’s sacred portraits have been associated with the contemplative prayer popularized by texts such as St. Ignatius’s Exercitia Spiritualia (Spiritual Exercises). One of the most popular devotional books in the history of Christianity, the Exercitia Spiritualia was written by the founder of the Jesuit order in his native Spanish and first published in Latin in 1548. The four-week program instructs the devotee to imagine using all five senses for full immersion in the contemplation of sacred episodes.

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Bust of Isotta Brembati, ca. 1550

Oil on canvas

21 5/8 x 18 1/2 in. (55 x 47 cm)

Accademia Carrara, Bergamo (58AC00087)

Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Lay Brother with a Fictive Frame, ca. 1557

Oil on canvas

21 3/4 x 19 7/8 in. (55.2 x 50.5 cm)

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main (904)

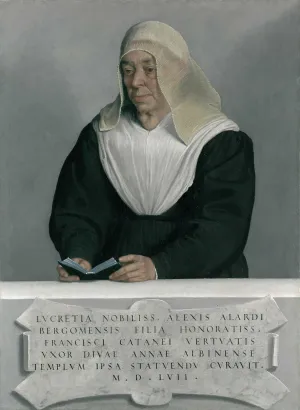

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Lucrezia Agliardi Vertova, dated 1557

Oil on canvas

36 x 27 in. (91.4 x 68.6 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915 (30.95.255)

Inscription: LVCRETIA NOBILISS. ALEXIS ALARDI / BERGOMENSIS FILIA HONORATISS. / FRANCISCI CATANEI VERTVATIS / VXOR DIVAE ANNAE ALBINENSE / TEMPLVM IPSA STATVENDV CVRAVIT. / M.D.LVII. [Lucrezia, daughter of the most noble Alessio Agliardi of Bergamo, wife of the most honorable Francesco Cataneo Vertova, herself founded the church of Sant’Anna in Albino. 1557].

The inscription credits the noblewoman Lucrezia Agliardi Vertova with founding, in 1525, the Carmelite church and convent of Sant’Anna in Moroni’s native Albino, where the portrait hung until the Napoleonic suppressions of the late eighteenth century. Widowed at a young age, Vertova appears to have been a tertiary of the convent. The longstanding identification of her as its abbess is unsupported by documentary evidence. She wears a brown dress, clasped partlet, and veil that are appropriate to her social standing and not, as has been proposed in the past, the costume of a nun.

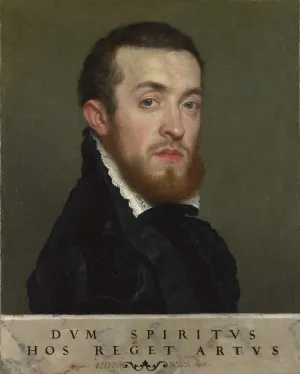

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Bust Portrait of a Young Man with an Inscription, ca. 1560

Oil on canvas

18 5/8 x 15 5/8 in. (47.2 x 39.8 cm)

The National Gallery, London; Layard Bequest, 1916 (NG 3129)

Inscriptions: DVM SPIRITVS / HOS REGET ARTVS [As long as breath animates these limbs], from Virgil’s Aeneid IV, 336; below, in gold-colored ink in a different script, ANNOR XXX [of thirty years].

© The National Gallery, London

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Portrait of a Young Woman, ca. 1575

Oil on canvas

20 3/8 x 16 3/8 in. (51.8 x 41.5 cm)

Private collection

Photo Michael Bodycomb

The unidentified young woman, probably from Moroni’s native Albino, wears a piercing expression and a sumptuous dress apparently of brocaded silk with silver wire. Such textiles (see the fragment of brocaded velvet) challenged artists to convey various materials and their effects. For example, Moroni communicates the shimmer of the textile’s silver wire through fine, slightly undulating lines of white paint.

Italian or Spanish

Fragment of Brocaded Velvet, 16th century

Composite fragment of red cut velvet voided on a blue ground with a pattern weft of yellow silk and paired drawn wire and details brocaded in silver and silver-gilt filé bouclé

11 3/8 x 22 3/4 in. (28.9 x 57.8 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in honor of Olga Raggio, 2002 (2002.494.598)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York / Art Resource, NY

Photomicrograph of velvet fragment at 20x magnification

Photo Cristina Balloffet Carr, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

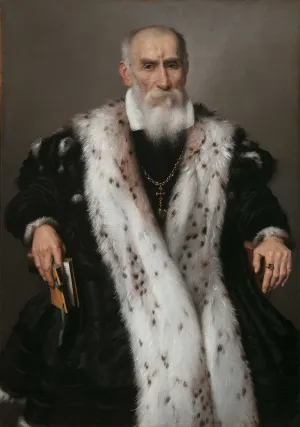

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1575−79

Oil on canvas

19 1/4 x 16 1/2 in. (49 x 42 cm)

Private collection

Photo Michael Bodycomb

Like most of the women Moroni painted, the sitter wears clothing and accessories that display her wealth and status, and there are no identifying attributes or inscriptions. Her pendant cross, like that worn in the full-length portrait of Isotta Brembati, is suspended from a pearl necklace.

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Alessandro Vittoria, ca. 1551

Oil on canvas

32 1/2 x 25 5/8 in. (82.5 x 65 cm)

Gemäldegalerie, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (78)

KHM-Museumsverband

The sculptor Alessandro Vittoria owned at least five painted portraits of himself by different artists. Presumably, this is one of the “two large portraits” of him mentioned in the inventory made after his death. The thinness of the painted flesh on the face and the depiction of a figure, with a rolled sleeve, in the process of studying, displaying, or working on a sculpture seem to anticipate Moroni’s Tailor. The portrait was probably painted about 1551, when both painter and sculptor were in Vittoria’s native city of Trent.

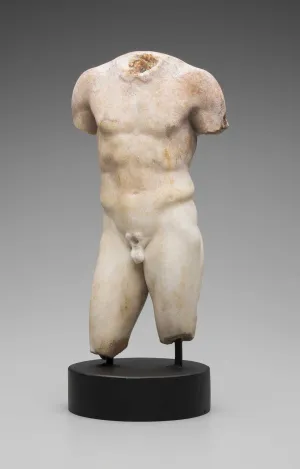

Roman

Nude Male Torso, 2nd century CE

Marble

14 1/4 x 7 1/4 x 3 3/4 in. (36.2 x 18.4 x 9.5 cm)

Detroit Institute of Arts; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John L. Booth (64.575)

Detroit Institute of Arts / Bridgeman Images

Giovanni Battista Moroni (1520/24–1579/80)

Gabriel de la Cueva, dated 1560

Oil on canvas

44 1/8 x 33 1/8 in. (112 x 84 cm)

Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin (79.01)

Inscription: AQVI ESTO SIN TEMOR / Y DELA MVERTE / NO HE PAVOR. [I am here without fear and of death I have no dread]; below, “M.D.LX. / Io: Bap. Moronus. p.” [1560 / Giovanni Battista Moroni painted it].

bpk Bildagentur / Staatliche Museen, Berlin / Jörg P. Anders / Art Resource, NY

One of Moroni’s most prestigious sitters, Gabriel de la Cueva y Girón, Count of Ledesma and Huelma, became viceroy of Navarre in 1560, fifth duke of Alburquerque in 1563, and served as governor of Milan from 1564 until his death in 1571. How and when he and Moroni met is unknown. They may have been introduced by Isotta Brembati or others among the pro-Spanish elite in Bergamo. The Spanish inscription reportedly recurs in the dukes of Alburquerque family history. Here, it draws attention to the sitter’s prominently displayed rapier.

Northern Italian

Rapier, ca. 1550/60

Steel, gilt iron, wood, brass and copper wire

46 7/8 x 10 in. (119 cm x 25.5 cm overall)

Imperial Armoury, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (A 683)

KHM-Museumsverband

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Bearded Man with a Letter, dated 1561

Oil on canvas

37 5/8 x 29 1/8 in. (95.5 x 73.3 cm)

Private Collection, courtesy Fabrizio Moretti

Inscription: On the column fragment, M.D.LXI. / Io. Bap. Moronus. p. [1561 / Giovanni Battista Moroni painted it]; on the letter, Mag. co ; Batt. / Marini (?) / Bergamo.

© Gianni Canali

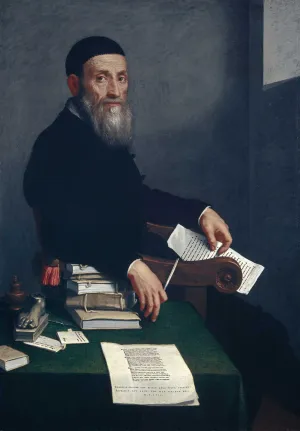

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Giovanni Bressani, dated 1562

Oil on canvas

45 3/4 x 35 in. (116.2 x 88.8 cm)

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh; Purchased by Private Treaty, 1977 (NG 2347)

Inscriptions: On the base of foot-shaped inkstand, IO: BAP. MORON. / PINXIT QVEM NON VIDIT [Giovanni Battista Moroni painted him whom he did not see]; on the bottom of the sheet of paper in the foreground, CORPORIS EFFIGIEM ISTA QVIDEM BENE PICTA TABELLA / EXPRIMIT, AST ANIMI TOT MEA SCRIPTA MEI. / M. D. LXII. [This painted picture well depicts the image of my body, but that of my spirit is given by my many writings. 1562]

National Galleries of Scotland

Arsenio

Giovanni Bressani, ca. 1561

Bronze

2 1/16 in. (5.3 cm)

Collection Mario Scaglia

Inscriptions: Obverse, IO. BRESS. BER. POE. ILL. ÆT. ANN. LXX [Giovanni Bressani of Bergamo, illustrious poet, aged seventy], signed APΣEN EΠOIH [Arsenio made it]; reverse, CVIQVE. IVXTA. MERITVM [To each according to merit].

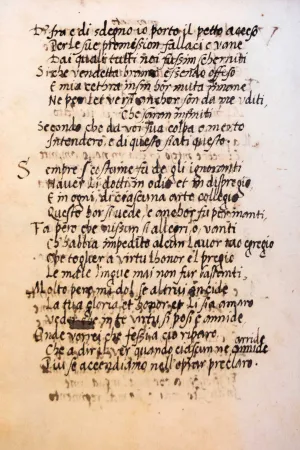

Stefano di Virgilio

Giovanni Bressani (1489/90–1560)

Prose e poesie, 16th century

Folio 78 (verso), 248 folios

8 1/8 x 6 1/4 in. (20.5 x 15.8 cm)

Biblioteca Civica Angelo Mai e Archivi Storici, Bergamo (MA 145)

This collection of poems presumably records Giovanni Bressani’s handwriting. In Moroni’s portrait of Bressani, the writer holds a piece of paper on which is written a poem beginning with the word sempre (always). This may have been chosen in the context of memorial — Bressani’s spirit (his writings) lives on after his physical body has perished — and may also refer to a specific poem. The only poem by Bressani that begins with the word sempre is displayed here and begins nearly halfway down the page.

Giovanni Battista Moroni

The Tailor (Il Sarto, or Il Tagliapanni), ca. 1570

Oil on canvas

39 1/8 x 30 1/4 in. (99.5 x 77 cm)

The National Gallery, London (NG 697)

© The National Gallery, London

French

Shears, 16th century

Iron

11 in. (28 cm)

MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art, Vienna (F 357)

MAK / Hanady Mustafa

Portrait of a Gentleman and His Two Children, ca. 1572–75

Oil on canvas

49 3/8 x 38 5/8 in. (125.3 x 98 cm)

National Gallery of Ireland Collection, Dublin; Purchased, 1866 (NGI 105)

Inscription: On letters, “Al Mag. Sig. Albino”; “ Albino.”

© National Gallery of Ireland

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Gabriele Albani (?), ca. 1572–73

Oil on canvas

43 1/4 x 30 1/4 in. (110 x 77 cm)

Private collection

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Gian Ludovico Madruzzo, ca. 1551–52

Oil on canvas

78 5/8 x 45 5/8 in. (199.8 x 116 cm)

Art Institute of Chicago; Charles H. and Mary F.S. Worcester Collection (1929.912)

Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Lucia Albani Avogadro, called La Dama in Rosso (The Lady in Red), ca. 1554–57

Oil on canvas

61 x 42 in. (155 x 106.8 cm)

The National Gallery, London (NG 1023)

© The National Gallery, London

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Isotta Brembati, ca. 1555–56

Oil on canvas

63 x 45 1/4 in. (160 x 115 cm)

Fondazione Museo di Palazzo Moroni, Bergamo – Lucretia Moroni Collection

Spanish

Pendant Cross with Emeralds, 1575–1650

Gold, emeralds, enamel, pearls

3 7/8 in. (9.8 cm)

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; Museum purchase, 1945 (57.1745)

Venetian

Fan Handle, ca. 1550

Gilt copper alloy, pierced and engraved; modern feathers

7 x 3 1/4 in. (17.8 x 8.3 cm)

Victoria and Albert Museum, London (105-1882)

© The Victoria and Albert Museum

Venetian

Marten’s Head, ca. 1550–59

Gold with enamel, rubies, garnets, and pearls; modern pelt; synthetic whiskers

L. 3 5/16 in. (8.4 cm) (jewel only)

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore; Museum acquisition by exchange, 1967 (57.1982)

Faustino Avogadro, called Il Cavaliere dal Piede Ferito (The Knight with the Wounded Foot), ca. 1555–60

Oil on canvas

79 5/8 x 41 7/8 in. (202.3 x 106.5 cm)

The National Gallery, London (NG 1022)

© The National Gallery, London

German

Sleeve of Mail, 16th century

Steel, copper alloy

15 11/16 x 13 in. (40 x 33 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Prince Albrecht Radziwill, 1927 (27.183.29)

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Giovanni Gerolamo Grumelli, called Il Cavaliere in Rosa (The Man in Pink), dated 1560

Oil on canvas

85 x 48 3/8 in. (216 x 123 cm)

Fondazione Museo di Palazzo Moroni, Bergamo – Lucretia Moroni Collection

Inscriptions: On the fictive relief at lower right, MAS EL ÇAGVERO QVE EL PRIMERO [More he who follows than the first]; on the stone fragment at bottom right, M.D.LX / Jo. Bap. Moronus [1560 / Giovanni Battista Moroni].

Photo Mauro Magliani

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Bernardo Spini, ca. 1573−75

Oil on canvas

77 1/2 x 38 5/8 in. (197 x 98 cm)

Accademia Carrara, Bergamo (58AC00082)

Inscription: BERNARDVS SPINVS / OBYT AN. MDCXII / ETATIS LXXVI [Bernardo Spini died in the year 1612 aged 76].

Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

Giovanni Battista Moroni

Pace Rivola Spini, ca. 1573−75

Oil on canvas

77 1/2 x 38 5/8 in. (197 x 98 cm)

Accademia Carrara, Bergamo (58AC00083)

Inscription: PAX RIVOLA SPINVS / OBYT AN. 1613 ETATIS 72 [Pace Rivola Spini died in the year 1613 aged 72]

Fondazione Accademia Carrara, Bergamo