Oval Room

Portrait of a Young Man, ca. 1517–18

Oil on canvas

28 1/2 x 22 1/2 in. (72.4 x 57.2 cm)

The National Gallery, London; bought, 1862

© The National Gallery, London

Although this work was long believed to be a self-portrait, the sitter's identity remains uncertain. Scholars have debated the object he holds as the key to his identity, suggesting it is a block of clay or marble (possibly indicating a sculptor), a brick, or a book. Related drawings (Study of a Young Man and Study of a Young Man) show the sitter holding the latter.

Study of a Young Man, ca. 1517–18

Red chalk

7 3/8 x 4 9/16 in. (18.8 x 11.6 cm)

Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence

Recto

Courtesy the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo

The drawings on the recto and verso of this sheet and another of the same title trace Andrea's development of the twisting figure, which reaches its fullest expression in his Portrait of a Young Man. Here, he experimented with the figure looking over his shoulder to the right, resting his elbow on an upright book.

Study of a Young Man, ca. 1517–18

Red chalk

5 1/8 x 4 15/16 in. (13 x 12.6 cm)

Galleria degli Uffizi, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Florence

Verso

Courtesy the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo

In this drawing, Andrea seems to rotate the subject of another Study of a Young Man to gaze directly at the viewer. He captures the intensity of his gaze with a firm impression of chalk representing the left eye, establishing the impact of the painted sitter as he confronts the viewer with shadowed eyes.

St. John the Baptist, ca. 1523

Oil on panel

37 x 26 3/4 in. (94 x 68 cm)

Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence

Courtesy the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo

This sensuous depiction of the luminous, handsome young saint was commissioned by a wealthy Florentine banker for display in his home. John's muscular body recalls that of Michelangelo's David. Standing in a rocky outcropping with his attributes of reed cross, camel skin, baptismal bowl, and proclamatory scroll held closed in his hand, he looks up to the source of divine radiance, enacting his role (as declared in the Gospel of John) as witness to the light of Christ.

Study for the Head of St. John the Baptist, ca. 1523

Black chalk

13 x 9 1/8 in. (33 x 23.1 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Woodner Collection

Drawn at the same scale as the painting it prepares, this head study must have been produced late in Andrea's design process and may have been transferred directly to the panel. The artist's handling of chalk brings to life the adolescent's features — playfully tousled hair, eyes looking askance, and lips slightly parted — and underlines that the sacred beings in Andrea's paintings were often rooted in models of flesh and blood.

The Medici Holy Family, 1529

Oil on panel

55 1/8 x 40 15/16 in. (140 x 104 cm)

Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence

Courtesy the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo

This depiction of the Virgin and Child with St. Elizabeth and her son, St. John the Baptist, under a stormy sky epitomizes the solemn, sacred paintings for which Andrea is best known. The pentimento in Christ’s leg is an insight into Andrea's development of the composition, a process further illuminated by preparatory drawings like the Study of the Head of an Old Woman and the infrared reflectogram of this painting.

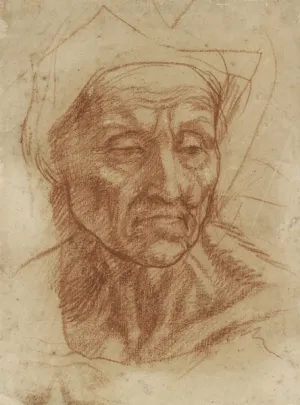

Study of the Head of an Old Woman, ca. 1529

Red chalk

9 13/16 x 7 5/16 in. (25 x 18.6 cm)

The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; presented by a Body of Subscribers, 1846

© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

For the pensive visage of St. Elizabeth (Mary's cousin) in The Medici Holy Family, Andrea generously applied red chalk to convey the wrinkled skin and crevices of the face of the older woman who miraculously conceived John, the prophet and baptizer of Christ. The drawing may have been produced before the full composition had been established for Andrea uncharacteristically included part of the figure that ultimately would not be painted: in the painting, her neck is obscured by the head of her son.